New Forest Records: The connection between forest, people and life

In spring, European sweet cherry (Prunus avium) will have a gorgeous flowering period, which is one of the most beautiful native tree species in Britain.

△ Umbrella of European sweet cherry with white petals (Source: Plant Wisdom)

European sweet cherry, also known as cherries, has been a favorite fruit for thousands of years.

European sweet cherry is a tree, belonging to Prunus of Rosaceae. Its plant can grow to 30 meters or even higher, and it belongs to a kind of tree with high height but relatively short life span.

△ In spring, clusters of delicate white sweet European cherries bloom on short thorns around smooth bark. Leaves rarely appear between flowers, and more leaves grow with the formation of fruits. The edible red cherry is a drupe that forms a single seed in the sweet pulp.

It is not only a native tree species in Britain, but also in most parts of Europe. Its natural distribution extends to the southernmost tip of North Africa and the edge of West Asia between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. Introduced into China and cultivated in Northeast China and North China.

Nowadays, it has been cultivated in Europe, Asia and North America for a long time, and there are many varieties. Naong, Fushou, Binku, Topaz, Dazi and other varieties are common in China.

△ European sweet cherry growing on the edge of a woodland in chilton Mountain. The distinctive horizontal cracks are called lenticels (named after their lenticular shape), which are clearly visible on smooth bark. The lenticels enable trees to breathe (exchange gas between internal tissues and the atmosphere) and enable these trees to be clearly identified in woodlands.

However, regarding the sweet cherry in Europe, john evelyn wrote in his "Forest Records": "I planted this kind of tree myself and taught it to my friends. They all grow very luxuriantly. However, this kind of tree has not been accepted by forestry workers so far … "

It was England in the 17th century.

John Evelyn was a knowledgeable artist and naturalist in 17th century England. As one of the founding members of the Royal Society, he is the core of scientific revolution.

△ john evelyn, 1687

Evelyn’s greatest literary achievement is sylva, or, a discourse of forest-trees, and the promotion of timbers in his majesties dominions.

Forest Records was published in 1664, the first edition was printed by the Royal Society, and then it was reprinted three times in Evelyn’s life and seven times after his death. This landmark monograph on tree management was founded in 1662. As a report, it responded to the call of the Royal Navy to solve the problem of timber shortage in shipbuilding during the civil war and the blank period of political power. This book was written by an outstanding philosopher with the direct support of the king, reflecting the importance of wood in 17th century British society.

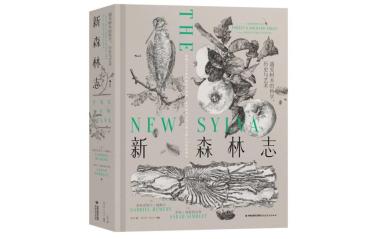

After 350 years, two British authors, with the support of the Forest Records Foundation, published The New Sylva to commemorate Evelyn’s works, which was inspired by Evelyn in both writing and thinking.

Sir Martin Wood, co-founder and trustee of Forest Records Foundation, said: "For 350 years, the roots of a forest oak tree have hardly changed. After all, this is only the life span of two or three generations for the growth of oak trees. However, in human society, the 17th century seems to be not only a past era, but also a different era. "

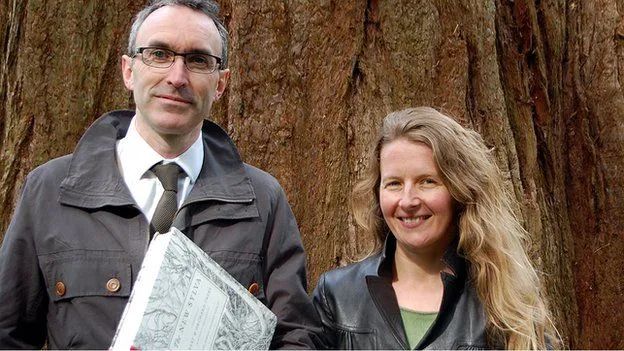

△ Gabriel Hemery (left); Sarah Simon Boelte (right)

The two authors of this book, Gabriel Hemeilu and Sarah Simon Boelte, describe the whole ecosystem of British woodlands through words and illustrations. They have revealed in detail the relationship between human beings and forests-those connections that are intertwined in life, the era of dislocation, permanence and smallness, all of which are connected with human life experience.

That’s why we love the forest.

New forest annals

[England] Gabriel Hemery [England] Sarah Simon Boelte

Forestry and early written language

Evelyn is not the first author who cares about trees and forests. In 1627, the philosopher Francis Bacon’s miscellaneous works of natural history, Sylva Sylvarum, was published, which also included the contents about trees. In the same year that Evelyn’s Forest Records was published, the 8th edition of Forest Collection came out. However, in England, the earliest records about forests and their management came from laws and regulations. According to Domesday Book, which was completed in 1086, the national forest coverage rate was about 15%. In 1215, Magna Carta was sealed under the branches of Taxus chinensis in Lannimide, and the records of land ownership also included those related to forests. In 1217, under the rule of Henry III, the Magna Carta gradually developed into the Charter of the Forest, giving free people the right to enter the royal forest, including the right to raise pigs and chop wood in the woodland. In 1457, England passed a bill to encourage tree planting; In 1483, in order to prevent grazing animals, another bill allowed enclosure actions against new woodlands. In 1503, based on the "complete destruction" of forests, Scotland promulgated a law to support tree planting.

△ King John sealed the Magna Carta under the branches of the European yew near Lannimide, Surrey, which was the basis of the British Constitution and eventually led to the demise of the forest law. The age of this European yew is unknown, but it must be more than 2,000 years old, and its circumference is at least 8.5 meters.

By the 16th century, the publishing and printing of books were mature, and perhaps the honor of "the first monograph on trees" should be awarded to Fitzherbert’s Book of Animal Husbandry published in 1523. This is a practical manual covering everything from horse management to beekeeping and ploughing repair, which contains practical suggestions on trees, such as grafting, cutting and selling, planting and pruning, and how to set hedges. Historians have been arguing about whether the author of this book is Sir Anthony, a well-known legal scholar and judge, or his brother John. In 1577, during the reign of Elizabeth I, Holinshed specifically pointed out in his Chronicles that "the planting of trees began for practical purposes". Twenty years later, John Gerard, a British pharmacist, published The Herb, or, Generic History of Plants, which was one of the most popular books in the 17th century. His writings have been passed down to this day because of their accuracy and liveliness. For example, his description of walnuts: "Flourishing on fertile and productive land, not ordinary highlands."

Forests in the 17th century

Seven years before Evelyn was born, Arthur Standish, an agricultural writer, published the Commons Complaint. This is an article approved by the king himself, focusing on slowing down the destruction of forests. In the article, out of the hope that "the country may always have enough wood for all purposes", he advocated planting trees on wasteland and proposed planting 240 thousand acres of forest. In the 17th century, people’s worries about the lack of wood were common. However, considering the importance of wood for domestic heating and cooking, industrial processes (usually charcoal is needed) and shipbuilding, this phenomenon is not surprising. The strategic understanding of national resources has matured during the 15th and 16th centuries. Henry VIII maintained a strong interest in British forest resources, especially in providing wood for naval shipyards. Wood reserves are under great pressure, and it is generally believed that trees with high wood value are being cut down indiscriminately and wasted on uses that could have been met with lower quality wood or shrubs. This led to the birth of the first Timber Preservation Act in 1543, sometimes called the Statute of Woods. This is a highly standardized law, which allows cutting down trees under strict guidance: 12 mature trees should be kept per acre;The cut shrubs must be closed to protect them from grazing animals, and so on.

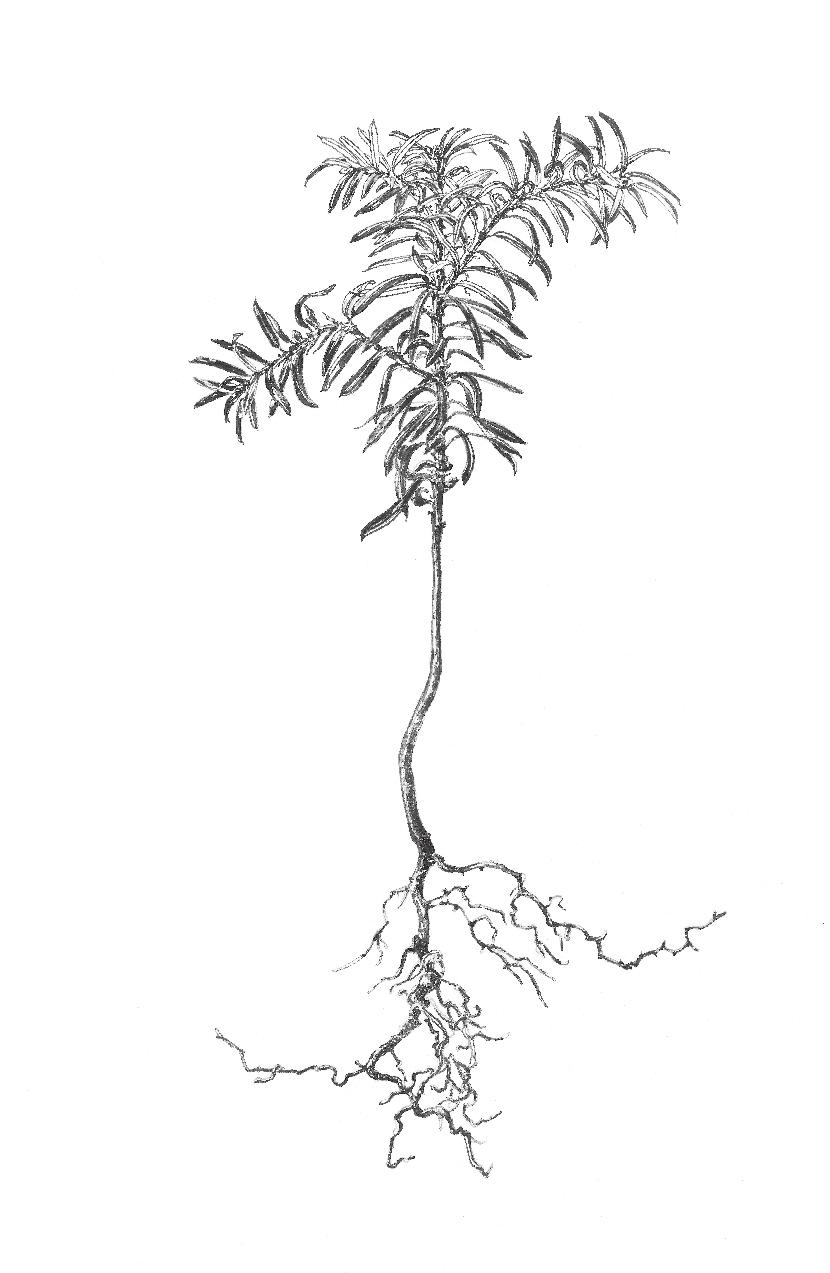

△ Three-year-old European Taxus seedlings. It germinates under the dense shade of the parent’s crown.

In the era of Elizabeth I, in 1588, a bill was passed to prohibit the "waste" of wood as fuel in the ironmaking industry. The bill stipulates that all suitable timber grown within 14 miles of navigable waterways can only be cut down for shipbuilding. By the late 16th century, the concept of plantation had spread from continental Europe to England. In 1580, people planted 13 acres of acorns in Windsor Park, which is one of the earliest records about oak plantation. James I, Elizabeth’s successor, also encouraged tree planting, but his successor Charles I thought that domestic forests were meaningless. What followed was the ravages of the British Civil War and the enclosure movement for agricultural land, which had a significant impact on the forest, leading to the great panic caused by the degradation of the forest when Charles II resumed the throne.

Historians don’t agree that the decrease of forest land and the shortage of wood supply are as serious as reported at that time. Some people think that this is because the courtiers exaggerated the status quo in order to urge Charles II to take action. A recent survey of evidence in Britain and its neighboring countries suggests that there may have been a local shortage of wood at that time, but it was impossible for there to be a general shortage of wood before the 18th century. It is estimated that there were at least 4 million hectares of woodland in England in the early 16th century, and there were still 3 million hectares in the mid 17th century. During the restoration period, although there were only 68 royal forests in poor condition, they still contained some excellent wood. Only one important bill was passed in the 17th century, namely the increase and preservation of timber in 1668. The promulgation of this bill led to the use of 11,000 acres of land for tree planting, which was regarded as the first afforestation movement led by the government. In this new forest, 6,000 acres of land were closed for planting trees, but under the influence of the London Fire and the Anglo-Dutch Wars, the planting work was never completed.

△ Ulmus minor subsp. angustifolia grows in Sherrington Manor near Sarma, East Sussex. These trees are skewed and become unstable, probably due to the disturbance of farming. In the distance is Sussex, which provides an important barrier for the prevention and control of dutch elm disease.

The navy’s action of obtaining wood from the forest is of great significance to the growth of trees and national politics. To build a single warship, such as Mary Rose, we know from the archaeological study of its wreckage that about 1,200 trees were consumed, which is enough to empty all the trees on 75 acres of land, equivalent to the area of more than 40 modern football fields. Moreover, the Mary Rose, built between 1509 and 1511, was not a particularly large ship. Like all ships of that era, most of the wood used to build it came from oak trees, but the keel was made of three big elms. Larger ships built later even used as many as 2,000 oak trees. From 1730 to 1789, it is said that the six major shipyards in Britain consumed 40,000 cubic meters of oak every year, which is equivalent to about 8,000 trees.

The navy has a greedy appetite for wood, and the woodland near navigable waters-which must be able to transport wood to shipyards-has been greatly affected. Evelyn wrote: "I heard that during the great expedition in 1588 (Spanish Armada), the commander gave clear instructions that they did not need to conquer our country and seek compensation for spoils after landing, as long as they ensured that there was no tree left in Dean’s forest." Although contemporary economists and even captains encouraged afforestation, their appeals had little effect.

△ stills of the movie "Scenery in Fog"

Shortly after the first publication of Forest Records, Captain John Smith wrote in 1670: "At one time, England was full of lush forests, and it was profitable to cut down these trees. But that era has passed. "

Original title: New Forest Records: the connection between forest and people and life

Read the original text